The Gazette uses Instaread to provide audio versions of its articles. Some words might not be spoken correctly.

Approximately once every two months, a train derails in the United States, spilling at least 1,000 gallons of hazardous materials. Since 2015, a review of federal derailment statistics revealed that nearly half of all derailments led to evacuations, and over a quarter resulted in a fire or explosion.

Additionally, a lot of the areas that are close to the rail lines are not equipped to protect people in the event that it occurs.

The Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland came to that conclusion after reviewing hundreds of rail safety reports and records and speaking with dozens of first responders and industry experts.

Additionally, a network of AI-enhanced video sensors provided the Howard Center with unprecedented access to rail data, enabling reporters to follow hazardous material shipments along 2,200 miles of rail lines between West Texas and the U.S.-Canadian border.

At least 130,000 rail cars with placards for hazardous chemicals traveled over segments of rail lines from Blaine, Washington, to Amarillo, Texas, during the previous six months, according to data given by a private corporation named RailState LLC. The investigation discovered that those vehicles went by more than 1,000 schools, 80 hospitals, and the residences of at least 2.5 million individuals who lived within a mile of the tracks.

According to Jamie Burgess, a hazmat training director at the International Association of Firefighters, “I think it’s fair to say that most communities are probably not aware of what chemicals are going up and down the railroads in their backyard, day in and day out.”

In the immediate aftermath of a hazardous derailment, first responders frequently lack the knowledge, skills, tools, and thorough planning necessary to react safely.

According to the U.S. Fire Administration, less than one in five fire departments around the country have a dedicated staff of hazmat specialists.

Local firemen depend on a network of assistance from neighboring departments, regional hazmat teams, state and federal officials, and railroad contractors to provide the knowledge and tools they might not have in the event of a catastrophic hazmat derailment. However, such teams may be hours away, so firemen may have to manage the developing situation alone.

In 2023, firefighters with specialized hazardous training took over an hour to reach the scene of a Norfolk Southern train derailing in East Palestine, Ohio.

Paul Stancil, a former senior hazardous materials accident investigator with the National Transportation Safety Board, stated, “It’s usually the first time that they’ve ever dealt with something like this, and they’re overwhelmed in the beginning.” In East Palestine, that was an issue. It is an issue on practically all sites.

According to industry estimates, at least 80,000 first responders participated in hazmat training programs supported by the railroad sector in 2024. However, according to U.S. Fire Administration statistics, this is only a small portion of the estimated 1 million career and volunteer firemen in the United States.

Rail is the safest means to move hazardous chemicals over land, according to Jessica Kahanek, a spokesman for the Association of American Railroads. In 2024, U.S. railroads safely transported over 2 million shipments of hazardous commodities.

At least 1,000 gallons of hazardous material were released in 57 derailments during the past ten years, according to a Howard Center review of federal statistics. Of the derailments, 16 resulted in fires or explosions, while 26 led to evacuations.

Firefighters dispatched to the scene of such derailments frequently encounter a serious issue: Many are unaware of the chemicals on board and the potential exposure concerns. Additionally, the need to provide that information right now has been postponed by federal authorities.

This month, East Palestine Fire Chief Keith Drabick wrote to federal authorities to express his disapproval of the delay and to request that they impose a more stringent schedule on railroads.

“The 2023 East Palestine derailment in my village highlighted a critical lack of timely communication with public safety about hazardous materials information involved in rail emergencies,” Drabick stated in a letter. He continued, “I am concerned that the derailment in my community could be repeated if regulators do not enforce it strictly.”

‘We were untrained … we were ill-prepared’

Communities may suffer severe repercussions if they are not ready for a hazardous spill.

Several tank cars carrying vinyl chloride, a highly dangerous and combustible chemical, plunged into a creek in Paulsboro, New Jersey, in 2012 after a derailment. A cloud of poisonous gas filled the surrounding area when one of the tank cars burst open.

At first, local police and volunteer firefighters approached the wreck without breathing apparatus, even standing in the cloud, because they were perplexed by the chemical that had been discharged. Investigators then discovered that many local residents waited hours in the exposure zone since the original evacuation area was too limited.

Symptoms of chemical exposure were reported by over 700 residents and responders.

According to a later NTSB assessment, the accident’s severity was exacerbated by the inadequate emergency response.

“We’ve never experienced anything of this magnitude in my entire career,” stated Chris Wachter, who was the police chief in Paulsboro when the incident occurred. “We lacked the necessary training. We weren’t ready for it.

Fire authorities in Paulsboro refused to be interviewed for this article. Gloucester County emergency authorities, who also declined to be interviewed, stated in an emailed statement that the county’s Hazardous Materials Team’s skills and linkages to local first responder organizations have seen “significant improvement.”

Only a small portion of the dangerous substances that frequently travel on the trains are represented by vinyl chloride. According to a Howard Center examination of RailState data, the most dangerous chemicals transported by train, aside from alcohol and petroleum, are sulfuric acid, chlorine, hydrochloric acid, and ammonia. All of these substances are extremely poisonous and can be fatal in large doses.

A crucial component of PVC plastic, which is utilized in building and packaging goods, is vinyl chloride. In water treatment facilities around the United States, chlorine is a common disinfectant. Fertilizer used on farms is made of ammonia and sulfuric acid.

In May 2021, 47 vehicles carrying hazardous chemicals derailed close to Sibley in northwest Iowa. Although there was a dense cloud of black smoke from the ensuing fire, no one was hurt. At the time, a Union Pacific representative stated that asphalt, potassium hydroxide, and hydrochloric acid were among the dangerous substances involved.

According to the Howard Center analysis, several dangerous compounds can travel over a thousand kilometers by train from the point of manufacture to the final consumer.

Federal dollars for preparedness getting tighter

Despite requests for more hazardous readiness for firefighters following the Paulsboro and East Palestine incidents, many departments lack the necessary resources.

Fire departments rely heavily on federal funds for equipment and training, but this financing is becoming less and less sufficient. According to Sarah Wilson Handler, vice president for grants at Lexipol, a company that offers consultancy services to police and fire agencies, grant program funding has drastically decreased in recent years, despite rising fire department expenses.

The Assistance to Firefighters Grant Program of the Federal Emergency Management Agency provided only $291 million of the approximately $4 billion in assistance that fire departments nationwide requested in fiscal 2024.

When it comes to emergency preparedness for harmful chemical spills, Port Huron, Michigan, cannot afford to take any short cuts. The 30,000-person city is situated on the Canadian border, across the St. Clair River from what residents refer to as the “Chemical Valley,” which is home to numerous chemical facilities and oil refineries in Sarnia, Ontario.

The United States imports a large number of these substances. St. Clair County’s emergency operations plan states that it is the nation’s second-highest trafficked border crossing for hazardous substances.

A mile-long tunnel beneath the St. Clair River between the United States and Canada has seen an average of 450 train cars bearing hazardous material labels during the past six months, according to RailState data. The presence of hazardous substance or hazmat residue in the vehicle is indicated with a placard.

More than 12,000 gallons of sulfuric acid were spilled when a Canadian National train derailed inside that tunnel in 2019. Under the guidance of the Environmental Protection Agency, the reaction relied on a network of assistance from state and local organizations, railroad hazmat experts, and Canadian authorities.

However, there is uncertainty regarding the future of federal assistance, notably the grant funds that the county hazmat team servicing Port Huron depends on.

FEMA has experienced significant staff reductions and layoffs in recent weeks, and President Donald Trump has frequently questioned the agency’s viability.

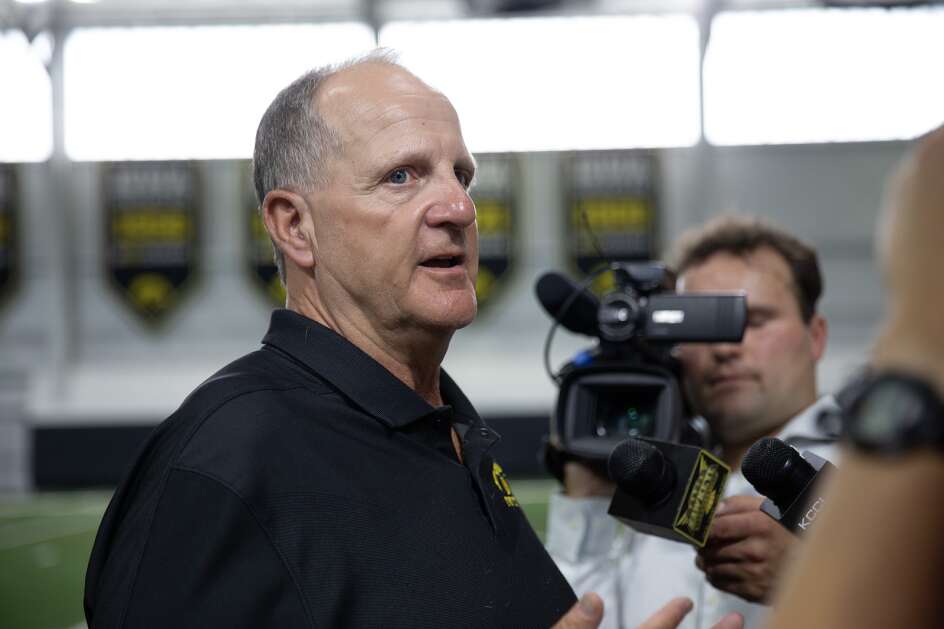

Federal money fluctuates, according to Port Huron Fire Chief Corey Nicholson, but he is concerned about the possibility of financial reductions. Spending on hazardous equipment and training becomes more difficult when funds stop coming in.

“Should I invest my money in the high-risk, high-frequency single-family home fires that I know will occur? Or should I invest in a lot of stuff that I’m unlikely to use? “What?” Nicholson inquired. “There’s so many mouths to feed and there’s only so much money to do it with.”

The Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland is funded by a grant from the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of newspaper pioneer Roy W. Howard.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.